|

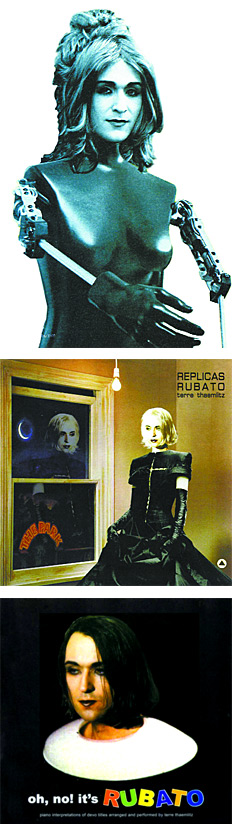

En contra de los clásicos encasillamientos, afirma: "No soy lesbiana". Y a continuación se formula esta pregunta en público: "¿Cuál es mi identidad sexual como drag queen transgénero vestida de hombre manteniendo relaciones sexuales con un hombre queer, andrógino y confundido con su género? ¿Y si él es gay? ¿Y si es bisexual? ¿Y si es lesbiana? ¿Y si es hétero? ¿Qué pasa si yo me visto de mujer? ¿Y si él se viste de mujer? ¿Qué se considera "sexo" y qué pasa si me está dando por atrás? ¿Y si no lo hace? ¿Y si estoy manteniendo una relación larga y monógama con esa persona?". Quien la vea aparecer, también puede atragantarse de preguntas: ¿Una drag queen haciendo temas de Kraftwerk en piano? Enseguida Terre se desmarca del estereotipo neodiva y aclara: "Soy una especie de drag queen antiespectacular". Basta de palabras, hay que ir y escuchar Die Roboter Rubato. Entonces quedará muy claro que estamos ante una obra compleja y profunda. El plan es desrobotizar a los Kraftwerk y aportarles feminidad. El texto interior cuenta el proceso compositivo y dispara contra "los padres del tecno" por misóginos. El resultado es un collage de fraseos de piano en estilo rubato (libre), con mucha cámara, en el que las melodías de los alemanes aparecen subliminalmente. Este puede ser un buen punto de partida para sumergirse en su extensa discografía que arranca en su propio sello Comatonse con algunos singles y con sus primeros álbumes en los sellos ambient norteamericanos: Instinct y Caipirinha. A partir del '97, sus ediciones comienzan a aparecer por el sello alemán Mille Plateaux, una referencia ineludible de la música electrónica más arriesgada (Oval, Kid 606, T. Köner, etcétera). Hasta su bancarrota en 2004, la discográfica edita varios de sus trabajos, partiendo del citado Die Roboter... hasta títulos como Love for Sale, Means from an End, Interstices, Lovebomb y otros dos álbumes que completan la serie de "Rubatos", en los que a través del piano aborda la obra de otros referentes del tecno pop como Gary Numan (Replicas Rubato) y de Devo (On no it's Rubato).

Hablando del asunto

En plena gira europea se contacta con Soy para hablar sobre su trayectoria y sus ideas. Haciendo historia, se diría, recuerda que el precoz interés en el tecno pop comienza en su Missouri natal. "El primer álbum que compré -a los 10- fue The Pleasure Principle de Gary Numan. Lo básico en USA era el rock'n'roll; sin embargo, a principios de los '80, algunas cosas de la new wave y el tecno pop llegaban a los charts. Los que solían molestarme escuchaban rock y eso afectó mi capacidad de apreciar esa música. Por eso optaba por aquellos grupos en los que no hubiera guitarras. Devo era el grupo perfecto porque estaba totalmente desprovisto (DEVOid) del optimismo de la música electrónica europea o japonesa."

A mediados de los '80 se traslada para estudiar en Nueva York, donde toma contacto con la militancia Glttb. "Comencé a participar en organizaciones políticas involucradas con temas de género, derechos reproductivos, liberación sexual y educación acerca del VIH. Las más destacadas eran WHAM! (Movilización y Acción por la Salud de las Mujeres) y Act Up (Lucha contra el Sida). Este fue el punto de partida para mis artículos sobre identidad y política. En aquella época el tema giraba en torno de la idea de 'Visibilidad'. Ser invisible era no existir. Ese fue el motivo del slogan de Act Up 'Silencio = Muerte'." Es a través de dichas experiencias que TT comienza a cuestionarse la noción de "comunidad" y desarrolla su idea acerca de la deconstrucción de las "verdaderas" identidades sexuales, algo con lo que va insistir a lo largo de su obra. "Para mí es importante deconstruir la forma en la que el mito de 'Comunidad' es manipulado tanto en el mercado como en la subcultura. Varios de mis proyectos han tenido como objeto tratar de dilucidar ese entrar y salir de las identidades, incluso confrontando las contradicciones en uno mismo. Se corre el riesgo de salir del closet para meterse en otro."

Paralelamente a esta etapa de militancia, comienza a descubrir material interesante en las disquerías del East Village y enseguida da sus primeros pasos como DJ.

"Mi primer empleo, en el '89, era en un bar asiático, con un video de Dead or Alive en rotación de fondo. Yo pasaba un deep house más bien instrumental que a nadie parecía gustarle demasiado. Por suerte después conseguí poner música en el club Sally II y hasta gané un premio underground como mejor DJ. Pero más tarde me echaron porque me rehusé a pasar Gloria Estefan." Al perder su empleo y no lograr encontrar otro lugar donde pasar la música que le gustaba, pensó en hacer esa música por sí mismo. Sin embargo, como bien dice, su primeros tracks no son música bailable común o "DJ-friendly". Cuando se vuelca a hacer ambient tampoco responde al género. En su música aparecen momentos de disrupción que rompen con lo típica espacialidad. Ya en sus primeros álbumes comienza a incorporar textos: "Son una forma de oponerme a aquellos músicos que se rehúsan a hablar coherentemente de su trabajo, y a la prensa musical que ve en esto una posibilidad para ubicarse en el rol de definir cómo esa música debe ser escuchada".

Sapo en otro pozo

La temática "Queer" no es algo muy común dentro del ámbito de la música electrónica. Para TT, el travestirse tiene que ver con tomar distintos contenidos culturales y ponerlos fuera de contexto, algo que también aplica a la hora de componer. "Mi interés en lo transgénero y el travestismo no tiene nada que ver con el esencialismo y con tratar de ser una mujer o tratar de escapar de mi cuerpo. Es lo mismo que trato de hacer con mi música tomando samplers y poniéndolos en un lugar diferente a su contexto original."

Cuando habla de su mudanza a Japón agrega que en Estados Unidos el maltrato físico y verbal era diario. "En cambio acá no.

Simplemente cuando no les gusta algo, lo ignoran. Para mí ese silencio es oro. De haber nacido en Japón, probablemente hubiera sido distinto y, seguramente, doloroso. Tiene que ver con mi contexto. Puedo decir que, visto a la distancia, creo que mucha de mi infelicidad tenía que ver con vivir en Estados Unidos y ese ambiente molesto. Es un lugar de mierda para vivir y espero no regresar más."

En el disco Love for Sale cuestiona a la "pink economy" y sostiene una postura controvertida sobre el matrimonio gay. "La cuestión del matrimonio gay es un buen ejemplo de algo por lo que se luchaba en los '90 con la organizaciones activistas de VIH en Estados Unidos. La cuestión era cómo extender los seguros médicos a la mayor gente posible. Se discutía sobre la igualdad en el matrimonio y los derechos de todo el mundo a casarse. De todas formas, este tema también pone en evidencia la opresión que ha significado el matrimonio a lo largo del tiempo de todos los géneros y sexualidades. Lo que opino no es que estoy contra el matrimonio gay sino en contra del matrimonio en sí."

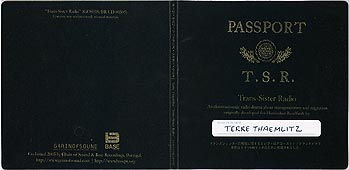

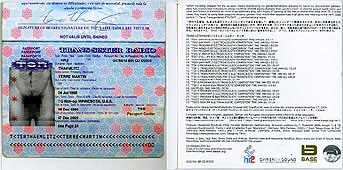

En 2006, el sello japonés Mule Musique recopiló en el disco Terre Thaemlitz Presents... You? Again?, parte de sus primeros singles que aún tenían alguna conexión con la música bailable. Mientras tanto, sus obras conceptuales continúan. Ha realizado especiales para radio, que luego edita en CDs que se consiguen sólo a través de su página. Este es el caso de Tran Sister Radio, que trata sobre las personas transgénero que viajan de incógnito, vestidas para corresponder con sus géneros documentados y cómo esto contribuye a la invisibilidad legal de esas personas. "No hay mucha información sobre cómo viajamos, o sobre cómo nuestra apariencia afecta nuestra capacidad para cruzar fronteras. También hablo sobre mis propios temores y preocupaciones al viajar, y cómo el hecho de ser expuesto como transgénero o queer podría complicar la aprobación de mi visa."

|

Full Interview in English

June 6, 2008

1) You mention Gary Numan or Haruomi Hosono to be important in your

queer formation. How and when did you start listening to synth pop

music?

The first album I ever bought was Numan's "The Pleasure Principle," at age 10. They used to play "Cars" at the local roller disco, which was where I got to hear a lot of disco and other dance music in the 70s. The US is much more rock'n'roll based than Europe, so although some new wave and techno-pop made it into the charts (especially between 1980-82), it was not at all popular in the area I grew up in, or with the kids around me. I had a lot of socialization problems as a youth, being harassed and ostracized for no real reason other than kids are vicious and need a target to attack, and the fact that the "mainstream" kids harassing me listened to rock music definitely affected my ability to appreciate "mainstream music." Although techno-pop records were difficult to find, when I did find them they were usually quite cheap. And in the 80s most record jackets still listed what instruments were being played, so I bought any record without guitars. At the same time, I was listening to old 78 rpm records of Fats Waller from my dad's collection, Rod McKuen make-out albums from the 60s, or anything terminally unpopular with the kids around me. I was totally suspect of any social connection with those kids, perhaps even more suspicious of the social ties between other "punks" and "fags" who collected in groups, somehow forming these little sub-groups of alienated clones like goth kids. If you want to imagine me in my youth, picture a gender-bender with hair between a mohawk and the lead singer of A Flock of Seagulls, blasting cassettes of techno-pop out of an 80s ghetto blaster sitting in the back seat of a beat-up pale blue 1960 Ford Falcon 4-door compact car barreling down a country road going nowhere... I think DEVO is the group that most typifies this techno-pop experience that was totally devoid (DEVOid?) of the optimism of European and Japanese electronic music. I think it's really something "American."

2) What was your experience as an activist within the GLBT movement

and why did you get away from this political expression?

In 1986 I moved to New York to attend college, and to try and escape the problems of my youth. I eventually became involved with various political organizations involved in issues of gender, reproductive rights, sexual liberation, and HIV/AIDS education. The most prominent of these were WHAM! (Women's Health Action and Mobilization) and ACT-UP New York (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). This was at a point when a lot of writings on identity politics were coming out, and everything seemed to revolve around the notion of "visibility." To be invisible was to be non-existant, and in conventional terms that was "bad." This was the crux of the ACT-UP slogan "Silence=Death." While I think there is something to visibility, particularly when focussing on issues of legislative rights, I was never able to really see myself in the identities we organized around. Either my gender or sexuality or race were seen by others as at odds with group agendas, "secretly" doing work for sub-caucuses where "White men" were not welcome, etc... Of course, this was preferable to working with the groups where "White men" dominated (such as the White-Gay-Male dominated main floor of ACT-UP), which ideologically I had very little in common with. All of these experiences finally helped me let go of the juvenile concept of "community," which I think is ultimately too ego-based. Of course, I invoke mythologies of community in my projects, but I also go to great lengths to deconstruct how those myths manipulate us, both within "the mainstream" and "subcultures." Identity is not singular, but schizophrenic and contradictory - for everyone, deliberately or not. I think many of my projects have been about trying to clarify this position of stepping in and out of identities, confronting these contradictions in myself, and how they tear a person apart - but my feeling is that it is better to consciously accept this tearing rather than dedicating oneself to a life of denial. Every time we step out of one closet we step into another...

3) How were your first contacts with house music and how did you

happen to become a DJ in the "queer" scene in NY?

I was going to school and living in the East Village, so I used to go into DJ record shops now and then. They were intimidating to enter, actually. Very clique-ish. But it was electronic music, so I had to check it out. Most tracks were shit, but every now and then you found something amazing... I first started DJ-ing in 89, I guess, at benefits for the Asian-Pacific Islander Caucus of ACT-UP, or doing mix tapes for their Pride Parade float. The first benefit was held at a horrible rice bar (Asian fetish bar) called Club 59, and I just hated the environment there, but I managed to talk the manager into letting me DJ once or twice on the weekends. It was a disaster. They usually just looped a video of a Dead or Alive concert, so people were really pissed off by my suddenly playing this rather minimal Deep House without vocals. That pretty much set the tone for my DJ career in New York. After that, I heard they were looking for a DJ at Sally's II, which is where I got my "underground Grammy" for best DJ, only to be fired a month later for refusing to play a Gloria Estefan record. The whole "scene" was a mess, totally closed to the "House Classics" everyone cherishes from that era. Those records were seldom played.

4) How do you feel when you see that house music- that was born as a

counterculture in which gays and black people played a leading role-

is now one more commercial genre within mainstream?

That process is totally typical, totally "normal," totally unsurprising... What can a person feel, other than numb? If the UK had not picked up on Acid House and regurgitated it back to the US through import records, I don't think it would have even become what it was in the US at that time. And of course, in the House scene, just as in the Tranny scene, people want to see themselves in the media, and totally judge their success by how visible they are - again, going back to the dreams of visiblity being equivalent to social acceptance - so the danger of your question is that it implies "Gays" and "Blacks" (and more specifically "Black Gays"!) are not already somehow placed within, contributing to and complicit with the "mainstream." In the late 80s/early 90s, the film "Paris is Burning" was the classic example of this debate - a film about the Latina and African-American Transsexual scene (which was the precise scene at Sally's II) made by a middle-class White woman. People were asking what gave her the right to represent "those people" or "us", depending on how one identified. The lines between exploitation and representation are always blurred. I am not saying they cancel each other out and make the situation acceptable. To the contrary, I am saying they are blurred and coexist in a violent struggle. Representation does not resolve the conflict. It may alter how we perceive that conflict, but it does not resolve it.

5) How did you leave the discotheque to get into the world of ambient

music and then to experimental? How do you accompany it with your

theory and your philosophical vision?

I left when I got fired from Sally's. It was just too emotionally draining, and physically exhausting (I was working a full-time office job as a secretary while DJ-ing at night). Since I couldn't find a club where people played the music I liked, but clearly the records were being made, I figured I would try making a record of my own and see if that led to any social connections... i guess that was my last investment into any dreams of "community." If you've ever heard my first record "Comatonse.000" you know it was not straight dance music, and not particularly DJ-friendly. In the same way, my ambient albums also contained moments intended to disrupt the "space-out" emphasis of the genre. My texts were also an intervention against musicians who refused to speak coherently about their work, and the music press who saw it as solely their role to define how music is to be heard. I have continued to work simultaneously in all of these various genres, from house to ambient to electro-acoustic, in audio and video and text and graphics... It wasn't so much a transition from one thing to another - not some career course, although it may look like that depending on what country you live in and what records were distributed there - but simultaneous projects that attempt to address the specific corners of the audio marketplace in which they exist, while hopefully contradicting each other and complicating any attempt to "course" my "career."

6) Don't you feel that in electronic music a certain macho hegemony

was reproduced, with little space for women and queer people?

Short answer: Yes.

Well, it's hard to ignore Disco as a queer genre of electronica, although it is true that the majority of festivals and events I am invited to perform at are incredibly non-Queer. This was the big turn-off of techno music in New York since the late 80s, that it was the Straight White Boy scene, and the majority of women attending were girlfriends dragged along by their boys. The gender issue is a bit more of an easy case to make, but I tend to think of it like the question of why aren't there more women producing pornography? It presumes that all media has potential appeal to all people, which overlooks the fundamental social structures which mediate our relationships to those media. I'm more interested in those relationships than in the sonic qualities or social reach of any particular genre.

7) What other queer artists do you identify or feel in tune with? Or

others than Ultra-red you worked with?

None, really. But, again, that implies some kind of value in identifying with notions of "community" which I am not particularly concerned with.

8) In your "Love For Sale" record you refer to the "pink economy" and

the inclusion of gays in economy as being just consumers or

functional to the economy? You also are also against gay marriage?

Can you explain your position?

The more one is able to see oneself reflected in the marketplace, in products, etc., the more one's identity is constructed by that marketplace, and the more restricted one's definition of self becomes. The political struggles around those constructs become more abstract, reified in the commodity level. They become "lifestyle choices" or "biological predispositions," and in that transition they lose their power as "alternatives" to anything. The issue of same-sex marriage is a good example, in that it was first really pushed into the media spotlight in the early 90s by US AIDS activists when it was conceded that socialized medicine was not a political possibility in the US. The question became how to extend health insurance to as many people as possible, and spousal coverage was seen as a solution. The practical nature of this push was soon lost to more esoteric humanist discussions of "marital equality" and the right of all people to marry. Personally, I feel this latter (and more common) debate simply reaffirms and reinvests in the ideological appeal of the matrimonial system which has oppressed people of all genders and sexualities for centuries. Meanwhile, I say this as someone who is married to a female partner, and without that legal connection I would have never been able to migrate to Japan. So my position is to continue actively expressing dissatisfaction with the systems we are forced to participate in, and not run away from hypocrisy. Hypocrisy is fundamental to struggle - it is the essence of being forced to do what one does not want to do because there are no alternatives. I am not against "gay marriage." I am against marriage. It's as simple as that. I can absolutely understand the social necessity for marriage in many spheres. But to want to celebrate queer participation in that system through ceremonies and all the acoutrements of "married life" is a self-inflicting violence I protest. There is a huge difference between saying, "I love my partner and we should have the same rights as a man and woman to get married," and saying, "The question of whether or how I love my partner is irrelevant to our demand for equal legal access to the rights of married heterosexuals - and we do demand those rights. They are the issue, the thorough issuance of which shall by effect destroy the sanctity of marriage (just as George W. Bush and other conservatives preach). We demand that destruction." Sadly, you don't hear many people putting it that way.

9) You moved to Japan, among other things, because of the people

treatment to queer persons. Are you happy with your decision? How do

you see USA from the distance?

It's not that Japan treats queers well. It's simply that when people in Japan don't like you they ignore you, which is quite different from the verbal and physical assaults vaulted daily in the US, so for me that silence is golden. If i were born in Japan, my relationship to that same silence would be totally different, and I imagine very painful. It has to do with background and context. As for how I see the US from a distance, I can say with confidence that much of my unhappiness while living there truly was because of the environment. It really is a shit place to live. I hope to never go back. I have no idea how I could ever emotionally deal with returning there.

10) You did a radio program called "Trans Sister Radio" in which you

refer to the problems transsexuals or transgender have at the

airports. Can you tell us about it and the passport you designed?

Perhaps it is simpler to show the image?

Basically, one section of that broadcast called "Trans-Portation" dealt with the ways in which transgendered people travel in cognito, dressed to match our documented genders, and how this contributes to the legislative invisibility of transgendered people. There is little documented about how we travel, or how our visibility affects our ability to cross borders. I also spoke about my own fears and concerns when traveling, how fears of being exposed as transgendered and/or queer could complicate my spousal visa status in Japan, and how these identities create legal grey areas that could cast suspicion upon my marriage despite my partner and I being of opposite documented genders. It's a very uncomfortable feeling on the one hand to worry about justifying the "legitimacy" of a marriage if government officials were to insinuate it was "fake," while on the other hand wanting nothing to do with these investments of authenticity into systems that are totally oppressive and exclusionary. It was a quite scary piece to produce, particularly since it was broadcast and released prior to my receiving permanent residence status (which I am happy to say I have since received). On a personal level I think that was one of the most emotionally challenging things I have ever done. But I think that, while there are clearly thousands of people organized around trying to secure more legal protection for transgendered people, there is also a need for documentation of the totally unheroic, unromantic, unglorified, unfulfilling ways in which we must betray ourselves in order to exist. I think our primary social condition is still the closet, and everyone is much more socialized by shame than pride, so we need some kind of counter-discourse to all of this bright-future-oriented discourse people are generating around what transgendered life should be... fuck what should be or could be, and let's really clarify what is.

11) In a way you got back to a more dance-oriented music as in your

beginning. Can you tell us how is your work as a DJ, what criterion

you use to choose what you play and what are the things that you feel

have changed since you began? In certain experimental electronic music there is a certain phobia

regarding dance music which is considered as a minor genre, you adopt

deep house and disco music without any preconception.

Again, this is not about a transition toward or away from certain genres. I have been working in all of these genres all along. It is about the economic shifts of the marketplace, and how those shifts affect distribution and visibility. Since Mille Plateaux went under in 2003 I have not had a label to work with in the electroacoustic genre. I do consider my electroacoustic radio dramas "Trans-Sister Radio" and "The Laurence Rassel Show" to be in the same vein as my Mille Plateaux albums, but they are distributed differently and also largely ignored by the music press. So when Mule Musiq issued a compilation of my old house vinyls and it was distributed in Europe by Kompakt a lot of people saw this as a kind of shift in my productions toward dance music, but in fact it was all old material they had simply not heard before. I guess I should point out people can buy any of my projects in any genre through my website comatonse.com. I'm not sure how to describe my criterion as a DJ. And of course people continue to insist my club oriented music is "soulful" or "spiritual" in sound, which is totally offensive to me (as a social-materialist), but I understand that is part of the ideological barrier club culture has erected around itself. I hope I am chipping away at that somehow, but who knows... so in that sense, I am actually drawn to dance music as a minor genre filled with preconceptions.

12) What has changed since the new musical formats and downloading

appeared? In your homepage there is plenty of material in MP3, are

you still against changes in the industry and the arrival of net

labels?

I have free MP3's online, but I am not set up to sell downloads. I cannot afford the bandwidth or server-side software development. I also do not trust online distributors, since I had problems with iTunes and others illegally selling my music without any agreement with me, and when I repeatedly sent them letters stating I was the legal owner of my works and asked them who they were paying royalties to I got no response. It was a nightmare getting my music removed from those systems. I am not opposed to file sharing or worried about "losing money" from this music that doesn't really sell anyway, but when the major industries who complain about piracy are illegally selling my music - music they clearly have no ideological investment in other than to expand their ability to generate revenues - that is exploitation plain and simple. I do not believe any of these changes in media format have altered the fundamental relationships between producers, labels and distributors. We are still fucked on every level. In fact, with the death of the album format we have an even more abstract relation to a connection between performance duration and media. If vinyl albums were limited to around 40 minutes due to sound quality issues, and CD's were 80 minutes, we are now generating for an endless void of possible downloads. Even if we produce an album, the fact that people might only download one or two tracks means we will only receive that fraction of the possible revenues from a complete album sale. Actually, I am in York, UK, right now where I am doing a project around this very theme (as part of the research project "New Aesthetics in Computer Music," York University). It will be the "world's first full-length MP3 album," which will be a single 31-hour 320kbps MP3 file filling a DVD-R. It is a piano solo entitled, "Meditation on Wage Labor and the Death of the Album." I've managed to record 13 hours so far... 18 hours to go in the next week. Of course, these days even a 31-hour album is not excessive enough, so I hope to release it as a 2-disc set with a video DVD of electroacoustic materials - the album title is "Soulnessless." I don't have any label yet - I can't imagine a label who'd be interested in putting it out the way I'd like it to be put out. It will probably get self-released on my Comatonse Recordings label to die in obscurity without distribution like so many other of my releases since Mille Plateaux went under. Coming back to the question of visibility, in some ways I'd much rather see things disappear than to deal with the legal games of the distributors. If people are too lazy to Google my name and find my website, and give up when they don't find my releases for sale on iTunes, fuck 'em. They aren't my target audience. And I feel an affinity for lost histories.

|